Family Matters

A Father in a Foreign Land

Dorrit Harazim

A week in which the personal dramas and court trials of three families collided in Rio de Janeiro once again. At the heart of the matter, an eight year-old boy.

rouched down on TAM Airlines’ infallible red carpet, which this time actually served a purpose, a passenger in transit to Rio de Janeiro tried to gather the cluster of documents that had fallen from his hands. Friday, October 17th, lobby of Guarulhos International Airport in Sao Paulo. He arranged his backpack, sent his two suitcases off again and headed to Gate 7. Guided by loudspeakers, he embarked on Flight JJ3522, en route to Galeao Airport. He settled into an aisle seat, took out a book of crossword puzzles in English, and dove into a half-finished puzzle.

rouched down on TAM Airlines’ infallible red carpet, which this time actually served a purpose, a passenger in transit to Rio de Janeiro tried to gather the cluster of documents that had fallen from his hands. Friday, October 17th, lobby of Guarulhos International Airport in Sao Paulo. He arranged his backpack, sent his two suitcases off again and headed to Gate 7. Guided by loudspeakers, he embarked on Flight JJ3522, en route to Galeao Airport. He settled into an aisle seat, took out a book of crossword puzzles in English, and dove into a half-finished puzzle.

David Goldman didn’t have the typical sleepy face one associates with someone who has just traveled over nine hours in coach on an international flight. It’s possible that his former occupation, when he crossed the airways between the United States, Europe and Japan as a model, helped to forever inoculate him against jetlag. Warned that a reporter would be sitting next to him on the flight and would be asking him questions about the legal labyrinth that he found himself trapped in four years ago, Goldman didn’t say no.

“I don’t have anything left to lose,” he said in a neutral tone, putting away his crossword puzzle book.

Goldman explained that he met Bruna, a Brazilian woman, in 1997 when they were 32 and 24, respectively, when they both lived in Milan. They fell in love and she got pregnant. They decided to cross the Atlantic and start a family in New Jersey, where Goldman had family ties and his own house. They were married there and their son was born there five months later, and they lived there for four years. Periodically, the three of them, or just the mother and son, traveled to Rio on vacation to see Brazilian relatives and grandparents.

In June 2004, Bruna and the boy took off from Newark Airport to go on another one of those Rio vacations. Days later, Bruna announced to David, by phone, that their marriage was over. She also told him that the most appropriate solution would be a divorce. She informed him that she and her son would not return to the US and urged David to come to Rio to formalize the separation. If he didn’t, he would never see his son again.

By retaining a minor in Brazil without her husband’s permission, Bruna violated an international treaty to which Brazil, the United States, and seventy-nine other countries are signatories. The Convention on Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction, signed in the city of Hague in the Netherlands in 1980, was approved by the Brazilian Congress in 1999, and was issued by Decree #3413 on April 14th of the following year.

Since the word “kidnapping” in Brazilian Portuguese is fatally associated with criminality and physical violence, a more appropriate translation would be the English term “child abduction,” which the Convention refers to, or perhaps it could be “country transfer and illicit retention of children.” In most of those types of kidnapping, the abductor is a parent who removes the child from the company of the other parent, travels with the child, and retains the child in another country.

According to the International Convention, the signatory country to which the child is brought is required to act in order to assure the child’s immediate return. The treaty also states that after the minor is returned to the state of his habitual residence, the litigating parties may fight for custody. But even so, they must do so in the responsible forum: in this case, in New Jersey.

Like all treaties, the Hague also includes exceptions and conflicting interpretations. And it’s using these meandering interpretations that lawyers and judges act.

David Goldman settled into his seat and fumbled for his backpack to discuss his perspective on seeing his son for the first time since 2004. Days before, the 16thFederal Court had granted his visitation request and he had left Newark on the first flight that had a seat available. Based on the decision, the visit would begin at 8pm on that unusually rainy and cold Friday and would end at 8pm on Sunday. It would be two days of, in family court jargon, “non-supervised contact” with his son—who David Goldman last saw when the boy was four years old. Now, he’s eight.

“I have no way of knowing how he will react when he sees me again,” Goldman said. “I’m not going to force it. Maybe he’ll be confused seeing that I’ve gone gray, but I know that he’ll recognize my hair. I’m going to wear casual clothes, like I used to wear during our American weekends.” Goldman said that he had separated two sets of photos so that his son could remember his life in the US.

In the first packet there were commonplace photos that could be in any young couple’s photo album. In the pictures he showed and commented on, there were trips to Disney World and to Canada, Halloween parties, father and son rolling in the snow and in fall leaves typical in the Northern Hemisphere where they lived. There were photos of birthday parties with the paternal and maternal grandparents, games with cousins Sean’s age, shots from Sean’s first school (Sean is the boy’s name), his little black cat, Tuey, and the first two pine Christmas trees planted by the family at the entrance of their house in Tinton Falls. “I’m a regular guy,” the American summarized.

In the second set there were equally happy images of the child, this time with his mother. “Maybe I won’t show these right away,” Goldman pondered. “First, I need to feel out my son’s emotional state.” The American reasoned a bit more, admitting, “To be honest, I’m the one that needs to prepare myself. To prepare myself for the possibility that the visit will be cancelled at the last minute, just another legal maneuver from the Lins e Silva family.” Before the flight landed in Galeao Airport, the name of the family that has made circles in Goldman’s imagination was constantly on his mind.

After divorcing unilaterally in Brazil, Bruna remade her professional and private life in Rio. She became a designer, opened a boutique in Ipanema and married the lawyer João Paulo Lins e Silva, son of the respected Paulo Lins e Silva and part of the Carioca clan that for more than 130 years and for five generations has provided legal assistance to the national elite. She changed her name to Bruna Bianchi Carneiro Ribeiro Lins e Silva and got pregnant. Sean’s half sister, baptized Chiara, was born on a Thursday last August. Bruna fell ill giving birth. There were complications, and she died. She was 34 years old.

“Mango juice, please…thank you,” said the American to the flight attendant, in Portuguese tinted by the years he lived in Milan, before switching back to English to tell his story. “Bruna and I lived in the same building, La Darsena, but we never crossed paths. One day, the owner switched our apartments so that we lived near each other, and bingo, it was fate. She was studying fashion in college, and I was a model, and we just fell in love.”

he plane landed in Rio. Goldman put the pile of photos back in their envelopes. He stopped to stare at a picture in which his son, in blue boots with his chest puffed up proudly, was holding a striped bass while fishing with his father. “And to think that this picture was taken a month before that Wednesday, June 16th, 2004. I must have looked like such a fool, taking them to the airport for a trip that I thought was just a vacation. Their return ticket was for fifteen days later, on a Thursday.”

he plane landed in Rio. Goldman put the pile of photos back in their envelopes. He stopped to stare at a picture in which his son, in blue boots with his chest puffed up proudly, was holding a striped bass while fishing with his father. “And to think that this picture was taken a month before that Wednesday, June 16th, 2004. I must have looked like such a fool, taking them to the airport for a trip that I thought was just a vacation. Their return ticket was for fifteen days later, on a Thursday.”

Three months before that date, Goldman had signed a document authorizing Sean’s trip with his mother since he wouldn’t be going with them to Rio. The document was valid until July 17th. “Bruna’s parents, who had bought property close to our home and were visiting, left on the same flight. They’re the only ones who can say how much they knew and how much they were part of their daughter’s decision to never come back. It was the last time I saw Sean.”

From that moment on, the case of Sean Richard Goldman combusted spontaneously, with the separation of a family leading to the multiplication of legal conflicts. But since the case falls under the secrecy of Brazilian justice, only the parties directly involved in the case have access to the court documents.

However, neither the New Jersey courts, where one part of the dispute takes place, nor the American media or the American citizen David Goldman fall under the jurisdiction of secrecy of justice in Brazil. Inevitably, the dispute became the talk of the town in various niches of Rio society, making the round among law offices and the media. It’s become so well known that emails allegedly sent by Paulo Lins e Silva, from last October, in which he refers to the century-long tradition of his family in the legal elite, found their way, albeit undesired, on to the World Wide Web.

“I get so annoyed by their arrogance when they suggest that the media investigate me, that I don’t have a real job, that my health is fragile, that I don’t have a home of my own to raise my child, or that Bruna always supported me,” says Goldman, who always uses the pronoun “them” to refer to the Lins e Silva family and his ex-wife’s family—opponents who, although invisible to him, he fears as having exceptional power and influence.

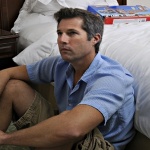

Seated at the edge of one of the two beds in his hotel in Copacabana, he responded to questions as he unpacked his bags. One of them was set aside for things he brought for the reunion with his son: new toys, Sean’s old toys from New Jersey, tee-shirts and hats, miniature cars and American candy. “I don’t know if he even plays with this type of car anymore,” he commented, as if to himself. He carefully showed a sticky green object: “I think it was a good idea to bring this rubber frog. Sean loved it and if he holds it, he might remember it, remembering how it feels in his hand. He’ll be able to see that the frog’s left leg still needs to be fixed.”

Seated at the edge of one of the two beds in his hotel in Copacabana, he responded to questions as he unpacked his bags. One of them was set aside for things he brought for the reunion with his son: new toys, Sean’s old toys from New Jersey, tee-shirts and hats, miniature cars and American candy. “I don’t know if he even plays with this type of car anymore,” he commented, as if to himself. He carefully showed a sticky green object: “I think it was a good idea to bring this rubber frog. Sean loved it and if he holds it, he might remember it, remembering how it feels in his hand. He’ll be able to see that the frog’s left leg still needs to be fixed.”

At 6:50pm, seventy minutes before the scheduled visit with his son at the address given by João Paulo Lins e Silva to the court, the phone rings in room 1420. Goldman answers. It’s his lawyer, who had spent five hours at court that day guaranteeing the conditions of the authorized visit, with two federal agents on alert just in case. He had three pieces of news for David Goldman.

The first was bad: “they” had entered a last-minute plea, asking the judge to veto the visit. The second piece of news was good: the judge denied the request. The third, a delay: the judge bumped the visit to 8am the following morning, a Saturday. This way, they would avoid exposing the minor to a potentially scary first visit in the dark on that cold and rainy night. “I can’t stand this rollercoaster anymore!” Goldman exploded. “I think they want to get me crazy.” An official from the American consulate in Rio, designated by the embassy to accompany Goldman on the visit, said goodbye and promised to come back the following morning. Calm and maternal, she told him she has four children. “How old are they?” Goldman wanted to know. “The oldest one is your son’s age.”

Since the night was already lost, the American continued to recite the story as he had begun on the plane. According to his account, Bruna and Sean had been gone only three or four days that year in 2004 when he received the shocking phone call: “David, we need to talk. Our love affair is over. Our marriage, too. I’ve decided to stay in Brazil with our son.” His young wife’s voice sounded metallic, cutting, incomprehensible. Bruna asked that he come to Rio as soon as possible to sign separation papers and to give her full custody of the child. She also wanted David to promise not to sue her in New Jersey courts. If he didn’t agree, he would lose access to his son. Once the initial shock was over, Goldman found a lawyer in his state named Patricia Apy.

But Bruna was quicker. Twenty one days after landing at Galeao Airport, she requested full custody and possession of her son at the Second Family Court in Rio. A month later, a judge in charge of the case awarded her custody. According to Patricia Apy’s interpretation, the judge failed to take into consideration that under the Convention on Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction, Sean was being retained in Brazil in an illicit manner.

In the civil suit number FD-13-395-05C, opened by David Goldman in the New Jersey Supreme Court, Bruna and her parents, cited as co-defendants, were ordered to appear in court to present their case in the Monmouth County Family Court, by 1:30pm on September 14th, 2004. It was also determined that “the defendant/mother will respond to this order by immediately bringing (within 48 hours of receiving the notification of this order) the minor Sean back to the United States, state of New Jersey, city of Tinton Falls.” Since she refused to comply with the order, the same court awarded the father, in March 2005, sole custody of his son.

Three court cases followed, with the boy growing up in the company of his mother, two maternal grandparents, and his stepfather. Every time Goldman entered a plea asking for Sean’s seizure so that he could be returned to his habitual residence, the plea was rejected by the Brazilian courts. On the federal level, Goldman says, voting was neck and neck, but time passed and soon enough, the feared twelve-month period ended: one of the exceptions under the Hague Convention on International Child Abduction allows, in article number 12, that once a year has passed after the illegal retention of a child, his integration into his new environment is to be taken into account. Translation: in a country like Brazil, where legal tradition favors that a child stay in the company of his mother, David Goldman’s case became much more complicated.

Over two centuries ago, an Italian father of more noble lineage than the American Goldman, had a similar experience. His name was Alessandro Fé d’Ostiani, a count and a diplomat. He married Rita de Souza Breves, the daughter of knight commander Breves, considered the richest Brazilian man of his time and whose lands extended from Itaguaí to Parati, from the mountains to the sea. The couple had a daughter, Paulina, who lost her mother when she was six years old, and was brought up under the care of her grandparents.

Having been transferred back to Italy, count d’Ostiani was forbidden by the Breves family to take his daughter with him. He had to appeal to the Emperor Pedro II and had a military escort commanded by Captain Piragibe to impose the order to find and collect his daughter. To no avail. Piragibe and his soldiers were thrown out of the property by armed men, and Fé d’Ostiani left Brazil empty handed. Knight commander Breves warned the count: it was the last time the Italian set foot on his property alive. Paulina only reunited with her father when she had grown into a young woman.

he most frequent question put to David Goldman is why, for four years of forced separation from his son, he never filed a suit to allow for visitation rights. “If I invoked my right of visitation, I would be implicitly accepting my son’s kidnapping,” he responds. “I took up the only legal battle that I consider conceivable: to be able to bring my son home, supported by the Hague Convention and the Supreme Court of New Jersey’s decision. All the rest—permanent custody or shared types of visitation should only be discussed once the original deviation was rectified and in the jurisdiction where our family resided.”

he most frequent question put to David Goldman is why, for four years of forced separation from his son, he never filed a suit to allow for visitation rights. “If I invoked my right of visitation, I would be implicitly accepting my son’s kidnapping,” he responds. “I took up the only legal battle that I consider conceivable: to be able to bring my son home, supported by the Hague Convention and the Supreme Court of New Jersey’s decision. All the rest—permanent custody or shared types of visitation should only be discussed once the original deviation was rectified and in the jurisdiction where our family resided.”

The umbilical cord connecting Sean to his biological father was maintained by airmailed gifts, animated greeting cards online and phone conversations that were subject to abrupt interruptions. “Whatever happens from now on, I already lost four years of my boy’s life,” said Goldman. “I will never know what it was like when he lost his first baby tooth. Or the second one. I make a great effort not to try to guess what kind of image he has of me.”

Every time that he came to Brazil to acquaint himself with the progress of the case along with Ricardo Zamariola Jr, his 28 year-old lawyer from Sao Paulo, David became anxious and discouraged. He never understood the legal entanglement of a case that seemed crystal clear to him. But after discussing legal details with his lawyer, he became familiar with the names of all of the judges involved, their decisions, and all of the details of the case. To try to reduce the emotional somersaults, he avoided traveling to Brazil alone. On the first trip, he brought his cousin. On the second, his father. On the third, he returned with his cousin. Each time—in 2005, 2006, and 2007—he went home to Tinton Falls, without Sean.

It was Bruna’s death this past August that definitively combined the dramas of the Bianchi, Goldman and Lins e Silva families. As soon as he found out his son had lost his mother, the American embarked on Delta Flight 121 on the morning of September 7th, , 2008 bringing Grandma Ellie, Sean’s paternal grandmother, whose fond relationship with her former daughter-in-law survived during troubled times. David was sure that given the disappearance of the maternal figure, this time his son would be returned to him by order of the court, without delay.

He then discovered that João Paulo Lins e Silva, Bruna’s widower, had filed suit in the Second Family Court in Rio de Janeiro asking for full custody and possession of Sean, claiming “socio-affective paternity.”

Goldman always gets upset when discussing this chapter of the story. “How is it possible,” he asks, “that a person without any blood relation to a child whose biological father is alive and well could be recognized as a ‘socio-affective father’ as the result of kidnapping? What do they want to do with my son? To give him the family name Lins e Silva and erase his original identity? It’s the most absurd of all absurdities, accepted by a judge of the law.” According to Goldman’s account, the same judge rejected his request to see his son after he lost his mother. Other sources guarantee that the denial split the mourning families.

To be so close to Sean and to find himself empty-handed yet again, David Goldman agreed to speak to reporters Uirá Machado and Cristina Luckner from Folha de S.Paulo, who wrote about the case on September 16th. In the name of secrecy of justice, the Second Family Court of Rio ordered the newspaper to abstain from publishing future stories. Ten days later, the Correio Braziliense newspaper wrote about the custody dispute in detail.

A report by Rede Record TV also caused João Paulo Lins e Silva and Bruna’s parents to file suit in court, requesting to censor the station. Claiming that the news crew had filmed the building where the Bianchi and Lins e Silva families live with Sean and baby Chiara, they presented the censorship request so that Record would abstain from producing, distributing and publishing any facts involving the minor. The prosecutor of the 37th Civil Court in Rio, on night duty, accepted the request.

It would be naive to hope that a story of an American child (Sean has dual citizenship), held in Brazil in violation of an international treaty, wouldn’t appear in the American media. Prior to agreeing to do an interview on NBC’s The Today Show– the morning news program with the largest audience in the US—he brought his case to authorities with the civil obligation to a constituent. The only person who avoided this responsibility, he says, was the president of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, the Democrat Joe Biden, Barack Obama’s vice presidential candidate. “I couldn’t vote for an administration that includes Sarah Palin, but Biden disappointed me so much that I don’t know who I’m going to vote for anymore,” said Goldman.

The governor of New Jersey, John S. Corzine, who was still a Senator at the time Goldman contacted him, has taken steps to help. In a long letter to a diplomat of the US serving in Brazil, he emphasized that he expected more effort so that the case could be resolved under the Hague Convention. He added that since Brazil and the United States were signatories to the treaty, the two countries should consider a private dispute about an abducted child to be of the same magnitude of any other international economic or environmental matter. He concluded requesting a follow up.

The State Department, for its part, through the Office of Children’s Issues (responsible in the US for the Hague Convention application), sent an official letter to the Brazilian entity that has the same function and asked that it obtain a fast solution along with the Brazilian courts. The Democratic Congressman Frank Pallone, serving his tenth consecutive term, dispatched letters in various directions, accusing the Brazilian Central Authority of not providing David Goldman with the appropriate assistance. Simon Henshaw, at the time Consul General in Rio, also sent letters to the Federal Judge of the Federal Regional Tribunal of the Second Region, and to the minister Nancy Andrighi, of the Superior Justice Tribunal, expressing the American Embassy’s concern with the legal decisions made until then, which were ignoring the Hague Convention application. The ambassador himself, Clifford M. Sobel, allegedly used diplomatic channels to convey the view that Sean’s temporary custody obtained by João Paulo Lins e Silva violated not only the Hague Convention, but the Brazilian Civil Code as well, which states that in the absence of a parent, the automatic custody is awarded to the other parent.

n Saturday morning, October 18th, when David Goldman would finally have visitation with his son, he waited with his Brazilian lawyer and an official from the American consulate for an hour on the sidewalk, while three court officers and two plain clothes federal police officers, accompanied by two building employees, went to look for the boy. After a lengthy delay, said David, the trio decided to wait inside a van with tinted windows until Sean was brought to them . They waited for three hours—for nothing.

n Saturday morning, October 18th, when David Goldman would finally have visitation with his son, he waited with his Brazilian lawyer and an official from the American consulate for an hour on the sidewalk, while three court officers and two plain clothes federal police officers, accompanied by two building employees, went to look for the boy. After a lengthy delay, said David, the trio decided to wait inside a van with tinted windows until Sean was brought to them . They waited for three hours—for nothing.

Sean wasn’t found. João Paulo Lins e Silva wasn’t, either. According to the court officers, the only people in the apartment were baby Chiara, Bruna’s parents and brother, and a nanny. David returned alone to his hotel on Atlantica Avenue, where he thought he would be spending the afternoon with his son.

In theory, the violation of a court order is a crime, even more so when dealing with a court-ordered visitation. But the times of knight commander Breves are gone and the child’s stepfather most certainly used a legal loophole to prevent Sean from seeing his father. After all, the era of Commander Breves is over. For Goldman felt that, again, that “they” could act as they pleased, at least with respect to his son. Still, he waited another week in his hotel room, not to run the risk of being absent during the next scheduled visitation date. As predicted, the visitation never happened. The only difference this time was that his lawyer was able to inform him of the denial three days ahead of time. This time, the court demanded a psychological evaluation of the boy before any visitation could take place.

In return, Goldman received two visits from court officers. When they wanted to serve him an order at 9pm, he thought it better to decline the invitation, asking that they come back the next day. One of the documents was a notification from the Third Prosecutor’s Office for Children and Adolescents, requesting he provide information about Sean in court. The other was a citation order and a summons, from the authority of Paulo Lins e Silva and João Paulo Lins e Silva, to respond to a supposed defamation and moral lynching campaign that was tarnishing the forty-year reputation of the plaintiffs. They also demanded that Goldman request, within 48 hours, that all of the media that had written offensive content about the plaintiffs, even on websites, immediately cease to do so. What’s more: the American must ask the press guilty of the infraction to rescind their stories, clarifying the inexistence of Sean’s kidnapping and the existence of a legal Brazilian decision regarding the temporary custody of the minor.

Two days later, accompanied by another lawyer, Goldman presented himself to the Public Ministry on Rodrigo Silva Street, next to the Carioca subway station. “When they read that I was being accused of renting a helicopter to fly over my son’s residence, even the court officials in the room laughed because it was so absurd,” he recounted later.

David Goldman still doesn’t have a helicopter, nor a job with a contract or fixed hours. He runs a fishing company for tourists that charges US$600 for a six hour fishing trip. “Despite the crisis, there are still a lot of Wall Street investors who lost money but not enough to give up everything,” he explained. He still pays mortage on his house in Tinton Falls, located in one of the wealthiest areas in New Jersey. During his married life with Bruna, she was the one who had a more regular professional routine—she taught Italian at St. John Vianney High School—and had a better family medical plan than her husband.

Goldman doesn’t hide the fact that he wasn’t financially prepared for four years of legal fees. He is a middle-class American. In the first twelve months alone, since he entered the plea to recover his son, he spent US$94,387.62 in legal fees to pay his American lawyer—she charges US$400 per hour. With the exception of the last trip to Rio, which was paid for by the NBC news program Dateline, which is preparing a special one hour report on Sean’s case, Goldman’s journeys to Brazil are weighing heavy on his wallet. Under different circumstances, perhaps he would have avoided a financial agreement in the New Jersey Court (FD-13-395-05c), in which he received the sum of US$150,000 from his former father and mother-in-law, the Bianchis, in exchange for removing their names from the case against Bruna as co-defendants.

A few hours before leaving Rio on flight CO 92 with a layover in Sao Paulo, Goldman explained that the night before, he was sitting at the hotel bar. He was approached by a talkative and eager Texan who told him a thousand and one stories. He tried to leave as soon as he could, fearing the Texan would ask him what he was doing in Rio.

“How do I explain my trip to Brazil in a single sentence?” he said. “It’s an entire life that’s in this trip. I even accept the fact that Bruna’s new husband has come to love Sean, but he’s my son, and he’s trying to take him away from me. Now that the stepfather has become the father of a baby girl himself, he should better understand the horror of it all.”